Filichia Features: “To Life!” to Fiddler On The Roof

Filichia Features: “To Life!” to Fiddler On The Roof

Does the musical that toasted “To Life!” have any life left?

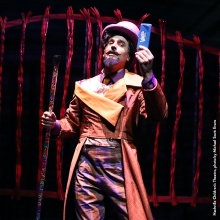

Oh, yes. Almost 50 years to the day that Fiddler On The Roof began rehearsals at the Lyceum Theatre in New York, Edina (Minnesota) High School proved that through the production it brought to Lincoln, Nebraska during the Thespian Festival.

The tears shed from both young and old audience members showed that the Stein-Bock-Harnick masterpiece still packs an emotional wallop. Even those who at intermission were saying that they’d seen it multiple times during its five-decade existence continued to be moved.

Better still, those experiencing the 1964-65 Tony-winning Best Musical for the first time seemed to be emotionally touched in the same the way their forebears had been. So while Fiddler wasn’t as au courant as the four other mainstage musicals that other high schools brought here -- the average age of those was fewer than nine years old – the applause for each Fiddler number and scene-blackout was no less powerful than those much younger musicals had received.

Right from the start, director Tony Matthes seemed to take the advice of a more recent Tony-winning smash: The Producers' opinion that “When you’ve got it, flaunt it.” Ally Nelson, The Fiddler who started the show, was a genuine violinist to whom Matthes gave a few more minutes of opportunity to show his ability. The audience was applauding before Tevye even took the stage.

They’d applaud Nelson at the end, too, thanks to a nice little bit that Matthes included. Tevye is the last to leave town, and usually he gestures that The Fiddler should follow him out. Here, The Fiddler helped Tevye by pushing his wagon. The suggestion was that Tevye would bring Russian-Jewish artistry to America.

Alas, teenagers – and those who direct them – have a tendency towards indication. In “If I Were a Rich Man,” Zach Farhat tapped the bottom of his chin three times when telling of Golde’s “double-chin.” Then he tapped his head and pointed out his brain on the last three syllables of “When you’re rich, they think you really know.”

On the other hand (and in Fiddler, there’s almost always another hand), one moment of indication seemed acceptable, even inspired. When Farhat sang ”I’d fill my yard with chicks and turkeys and geese and ducks,” he acted as if he were dispensing bread crumbs from his apron.

Farhat may well be the reason why Matthes decided to do Fiddler in the first place; the lad is a natural-born Tevye. He stood up to Russian authority without crossing a line that would get him in trouble. But when he arrived home, he was indeed “master of the house who had the final word” -- well, except when he had to deal with his wife Golde. Farhat was especially good when the meek Motel approached him to ask to marry his daughter and couldn’t find the words. This Tevye was a lion who roared with impatience.

By the way, here the men and boys in the audience came out with some hearty masculine laughter. They remembered when they went through this with the fathers of the girls they once wanted to date. See? Fiddler is still relevant.

Motel is the character who grows the most in Fiddler – from scared rabbit to successful self-employed businessman. Max Kile let us see the steady growth and had the transition come at the right time: when he donned his formal black top hat before his wedding. He had the look on his face that every Motel must have – one that says, “Today, I am a man.”

Matthes had quite a strong cast. Ben Weiman correctly had his Constable feel guilty at dispossessing the Jews, which was why he didn’t retaliate when Tevye snarled “Get off my land!” Julia Brooks managed to make Yente see herself as a career woman. And more I cannot wish you than to have a voice and presence as glorious as Tori Adams’ for your Hodel. This girl is a young Rebecca Luker, which is about as good a compliment as any musical theatre actress can get.

Rachel Winton did superbly when young Chava comes into the village to buy some necessities and is derided for being Jewish by Gentiles townies. The stage direction says that they “mock with a slight mispronunciation,” but Matthes had his actor make the mispronunciation quite pronounced: “Mazeltov, Kkkkkkkava,” which was his way of implying that the way Jews pronounced “ch” was stupidly overdone.

Fyedka is also a Gentile, but he not only rescued Chava from this persecution, but also endeavored to get to know her better. He was aware that the way to this woman’s heart was through her love of books, and so he offered her one. This lead to a small but important exchange of dialogue: after Motel came in and saw Fyedka -- who decided he’d better leave fast -- Motel noticed “You forgot your book,” Chava immediately said, “No, it’s mine.” This was Chava’s first rebellion against tradition, but she would soon have others. Rachel Winton was skillful in showing both the guilt of lying, the need to read and the desire to know more about this stranger.

When the time came for the Russians to disrupt Tzeitel and Motel’s wedding, Matthes shrewdly had these Cossacks come through the house. Few if any in the audience saw that coming, and the soldiers’ completely unexpected presence caused many to suddenly turn around, genuinely startled and quite unnerved. Matthes got what he wanted: he had Americans living 100 years later get a taste of what the Anatevkans had experienced. Of course it was only a hint, for the Anatevkans would now literally bear the brunt of the invaders. But if we could be rattled by the mere presence of people coming in behind us, we realized how much worse the total invasion of home was.

As the act ended, Matthes smartly brought Chava and Fyedka to the forefront and had them give a long look at each other. We inferred that they were both thinking the same thing: “Under these circumstances, can a Jew and a Gentile really consider marriage? Can we overcome this antipathy or must we find a way to forget about our love?” The question would be answered in Act Two.

Matthes had Golde hanging out laundry as “Do You Love Me?” began. So when Tevye began remembering their wedding day, Matthes had him go into the laundry basket, take out a prayer shawl and put it on her head to represent a wedding veil. If it appeals to you, use it.

Near show’s end, Yente brought two young boys to Golde, all to cement a match between the lads and Golde’s youngest daughters. Usually the two pre-teen boys are directed to look somewhere between disinterested and uncomfortable at being trotted out for display. Instead, Matthes made a clever move by having one of the lads smiling and waving to the girls, hoping to get either one’s attention, very willing and eager to meet his future bride.

Well, why not? Even the youngest children can buy into the traditions of old and see themselves as part of the system.

One reaction from the audience has changed in 50 years, and it’s a nice sign of our times. After Tevye had told Golde that he’d given Hodel and Perchik permission to marry, she said “Without even asking me?” – to which he roared “Who asks you? I’m the father!” The outraged sound that the high-schoolers in the audience gave made clear that they couldn’t believe that a husband would be so dismissive to a wife. They’ve become accustomed to marriages where spouses work together to make any major decision.

So does such a scene make Fiddler On The Roof “dated?” Think of it instead supporting the show’s main theme: another “tradition” that had needed to be reassessed has been happily broken along the way.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.