Filichia's Features: Welcome to the Junior Theater Festival, Part 3

Filichia's Features: Welcome to the Junior Theater Festival, Part 3

Saturday, Jan. 14 at 1:30 p.m. at the Junior Theater Festival. The students from all 63 schools and after-school musical theater programs have completed their presentations. If the kids were sky-high before their performances, they’re even more excited now. While a comparative few felt are mourning the lines they flubbed or the cues they missed, most students are deliriously happy with the way they performed and how they made their teachers proud. Let’s celebrate!

But the adjudicators who’ll choose the worthiest of the worthy have work to do. Over boxed lunches, they’re saying to each other, "You know the one I feel strongly about?" and "Considering how good they all were, should we just simply give another award?" Adds another, “Whichever one we choose, it's going to strike us all as Sophie's Choice."

The session is not solely about awards. Many adjudicators are telling their colleagues how they were touched by certain kids. There was the school that had been trying for nine years to raise enough money to get here, and this year finally did. Add to that the boy who once had a speech impediment, but thanks to constant performing, now doesn’t. And how about the girl with spina bifida who nevertheless managed to be part of a show?

The stories don’t surprise those who are hearing them. Many adjudicators are nodding slowly as they listen. Over the years, they’ve heard many such anecdotes that reinforced what they’ve known all along: that theater makes life better for so many kids. They’re not surprised that it’s happening again.

2:45 p.m. Steve Kennedy assembles a group of teachers. Won't it be fun to learn a dance number that they can perform with the at festival's end? The teachers give decisively affirmative head nods, so Kennedy starts his CD player. All grin when they hear Annie's original cast sing "You're Never Fully Dressed without a Smile." But Kennedy has a surprise for them: halfway through, the melody suddenly morphs into Lady Gaga's "Born This Way." That gets a collective burst of laughter from everyone. Kennedy waves it down and starts instructing: "Step forward, step right, dip your left hip." The “students” learn the routine with no trouble. Those who teach, can.

3:15 p.m. Here to share secrets of the trade are Broadway directors Jeff Calhoun, who’s readying Newsies for a March opening, and Baayork Lee, who’s come to the festival straight from Melbourne, where she’d mounted A Chorus Line.

That landmark hit has been a part of her life for almost 40 years. Lee was in director-choreographer-conceiver Michael Bennett’s inner circle, so she was in on those taping sessions that helped develop the musical. That led to her creating the character of Connie Wong and originating it on Broadway. “I get a great deal of pleasure and pride,” Lee has often said, “knowing that I created a role that young, diminutive Asian women will be playing for a long, long time.”

Calhoun quickly establishes his respect for those who work in education. "I still call my teachers and thank them," he says. "One reason I'd like to win a Tony is so I could acknowledge them in a nationally televised speech."

But he and Lee are not above putting the teachers on the spot. They pointedly ask them if they’ve created a rehearsal room that's nurturing, one with a great sense of humor and one where the best idea wins, no matter who came up with it. Says Lee, “When we were creating A Chorus Line, Michael always used to say, 'Let me hear more of your ideas! More! More!’ And that helped the show to be the show it is."

Lest people get erroneous ideas from optimistic show songs, Calhoun makes clear that while there’s no business like show business, everything about it is not appealing. "I scare the actors,” he admits, before telling why: “The ones who don't get scared are the ones who are meant to stay in the business.”

Time for questions. Nobody asks Lee, "So what was the notorious Michael Bennett really like?" or "What do you remember from when you were a little girl in the original The King and I?" Nostalgia is nice, but they all know that they won’t often be in a room with two New York theater veterans who have a combined 27 Broadway shows under their belts. They’ll seize the opportunity to ask such questions as "How important is formal dance training?"

Calhoun and Lee indicate that they’ve seen people succeed and fail with it and without it. “What people have to remember,” says Calhoun, “is that when you come right down to it, it’s blue collar work."

Asks one teacher, "What's the most important thing we can teach them?" Lee mentions "the importance of warm-ups. I'd rather lose an hour of rehearsal than skip those."

Calhoun’s answer: “Discipline.” He points out that while Broadway performers show precisely for half-hour call, London actors tend to show up as early as an hour-and-a-half before to prepare even more for their roles. Lee agrees, recalling with disgust how many performers in her 2006 revival called in “sick.” Says Lee, “I kept telling them, ‘I hired you because I wanted you, and not your understudy.”

But, says Calhoun, discipline is not all that teachers should stress: "There’s the balance of a healthy ego and humility," he says. The slow way he raises his eyebrows on this piece of advice shows that he knows that it’s not easy to achieve.

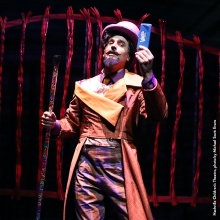

Jeff Calhoun - MTI's Flickr Album

The teachers feverishly jot down everything from Calhoun's "Steal from life" to Lee's "Honor the material." When the session ends some 90 minutes later and the teachers file out the room, they are animatedly chatting. The best possible scenario has happened: they’ve learned not only some new information, but they’ve also had reinforced that so much of what they’d been doing has been on the right track.

4:15 p.m. Court Watson holds, if not court, a session in which he tells the secrets of what he does for a living: set design.

Perhaps the festival’s powers-that-be have underestimated the interest that teachers would have in this subject, because they place Watson in most modest-sized room. Now there’s a standing-room-only crowd in front of him. Someone calls for additional chairs, and maintenance men soon arrive with 12 more. Yes, that allows a dozen to sit, but the open doors allow others who had arrived a bit late to crash the party. Now the room’s even more crowded.

But Watson’s delighted to have all of them – especially so that he can dispel one misconception: “While a lot of kids thinking that working on a set as a type of punishment for not being cast, let them see that they can make a living from it -- perhaps more than they can from performing," he says ominously.

For kids, he believes, may have more abilities in this area than they realize. “A Virginia teacher I know asked each student to design one scene from the show he was doing with them,” he says. “He found that a lot of their ideas were so good that he used many of them."

Watson has a few good ones of his own. “I designed an Annie Get Your Gun, a show that you’re absolutely required to do as written,” he says grimly. “That means that you have to include Annie's song, 'I'm an Indian, Too,' which doesn't seem politically correct these days. So I figured I might defuse anything offensive by playing it in silhouette behind a sheet." Watson’s slides show how effective this solution was.

While he says that "A set designer tells a story in a visual way," he tells of the necessity to knowing what the construction crew is enduring. "If you don't know how it's built, then you shouldn't be designing it," he insists.

Now the advice: “Build a ‘toe-rail’ to help your actors know where the edge of the set is.” … "Make the scene change part of the story." … "Don't paint on the flat itself, but on the fabric that'll cover it." …

"Make a point of recycling." … And when one is saddled with a terribly distressed piece of scenery, "Fix it or feature it."

Time for questions. “What’s this I hear that foam is hazardous to your health?” ("Not if you cut it with a saw."). "Should we prime bedsheets?" (“Yes.”) Even “What’s a good book on design?” is asked. (“Drafting for the Theatre")

A good deal of nuts-and-bolts information is dispensed. “Do you guys know Rose Brand?" Watson asks hesitantly, citing the New Jersey company that rents production supplies. “Communitytheater.org?” He’s pleased to see so many heads enthusiastically nod in response.

But far fewer knew of what he next suggests: “There’s a Home Depot 'oops' section where cans of mixed-color paint that didn't turn out quite right. Well, maybe they’re no good for your living room, but they might be good enough for your set. And don’t be afraid to go to a hardware store and ask what they're throwing out."

Fewer still know about this: “Build half a chandelier and put a mirror behind it. Not only is that cheaper,” he says, “but you only need half as much storage space for it, too.” When Watson sees he's given them even more two more entrees in the food-for-thought category, he gurgles with pleasure.

And yet, Watson’s most potent observation may be what he says about designing a set for a farce. "These shows depend on split-second timing,” he says, “so you have to work out with the director just the right number of steps to help the cast to get where they’ have to be on time.”

As the session ends, heads shake slowly from side to side out of admiration for Court Watson. The teachers leave the room, and head for the staircase. One looks at the many, many steps and says, “Boy, this’d never work for a farce.” Remembering Watson’s words may now be in the mind of each artist descending a staircase.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each . and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His newest book, Broadway Musical MVPs, 1960-2010: The Most Valuable Players of the Past 50 Seasons, is now available through Applause Books and at www.amazon.com.