Filichia Features: What a Leap of Faith!

Filichia Features: What a Leap of Faith!

They’re still talking about your wildly successful production of The Music Man, aren’t they? Oh, that dynamic actor who played Harold Hill! Ah, that equally potent actress as Marian Paroo!

They’re still talking about your wildly successful production of The Music Man, aren’t they? Oh, that dynamic actor who played Harold Hill! Ah, that equally potent actress as Marian Paroo!

Why not pair them again in Leap of Faith?

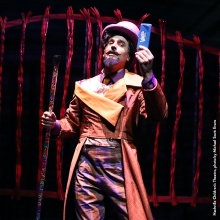

Leap of Faith’s Jonas Nightingale is described as “charismatic, complex and wired” in the stage directions. “When Jonas looks at you,” they say, “no one else exists but you.” Don’t those descriptions sound apt for Harold Hill? Similarly, Leap’s Marla McGowan is called “buttoned-down” – which certainly could apply to Marian the Librarian at the start of The Music Man.

Both shows tell of a con man who comes to a small Midwestern town where he fools most everyone except a perceptive woman. She eventually comes to care for him, and at each show’s end, he gives us the impression that he will settle down, mend his ways and become a surrogate father to a young man.

Harold in Meredith Willson’s 1957-58 Tony-winning musical preys on River City, Iowa’s fear that that the towns’ teens are being corrupted by the presence of a pool table in their community. “Your young men'll be frittering! Frittering away their noontime, suppertime, choretime too!” warns Harold.

Jonas in Alan Menken’s 2011-2012 Tony-nominated musical – set fewer than two hours away in Sweetwater, Kansas -- says that he too “can set their children straight.” But he’s intent on reforming the adults as well. Jonas has upped the ante on Harold’s mere lobbying for a boys’ band; he’s a preacher who ostensibly wants to clean out everyone’s souls, although he’s far more intent in cleaning out their wallets.

What’s interesting is that the shows are set precisely 100 years apart: The Music Man in 1912, Leap of Faith in 2012. Because of the many differences that a century can bring, Leap of Faith has much more of a bite – nay, a sting.

For example, Jonas in his first song says that “the economy sucks,” a vulgar term that Harold would never have used. Nevertheless, this is one of Glenn Slater’s very clever lyrics. By having Jonas say a semi-naughty word, he shows he’s an up-to-date a man of the people and not a boring sobersides. These days, more than any other time in history, a preacher needs to seem as if he’s au courant.

Both Harold and Jonas run into formidable career women. Marian is an anomaly in her town; if there’s another woman working nine-to-five in River City and teaching at night, we don’t hear of it. But that’s Marian: librarian by day, piano instructor by night.

Marla, on the other hand, has more responsibility in a job that a woman in 1912 wouldn’t have dreamed of (or even considered): town sheriff. That gives her more power over Jonas than Marian ever had over Harold.

She obviously has the respect of her townspeople, for hers is an elected office. On the other hand, Marian is considered the town’s scarlet-letter woman, because she was rumored to have had an affair with River City’s richest man.

We never learn conclusively what Marian did or didn’t do with “Old Miser Madison.” What we do know about Marla, however, is that she’s a widow who hasn’t been with another man on the scene in more than a thousand days. So while Harold and Marian don’t kiss until 18 songs have been sung, Jonas and Marla kiss after the sixth song, right before they head for bed.

What’s more, Marian has officially fallen in love with Harold before she allows him to kiss her; Marla frankly feels the need to have sex with that “charismatic, complex and wired” man who makes her feel that “no one else exists but her.”

Marian comes to love Harold because he makes Winthrop come alive by giving him a band uniform and a cornet. When Marla consorts with Jonas, she hasn’t seen anything that has made her care for him. As Cole Porter once wrote, “It’s a chemical reaction, that’s all.”

Marian sings that there were bells and birds that she respectively never heard ringing and singing “Till There Was You.” (It’s The Music Man's best-known song, especially because it’s the only Broadway show tune that The Beatles deigned to record.) Marla heard both that ringing and singing long ago but now is “long past dreaming” for “all that wishing” she made “came to nothing.”

That brings us to the difference between the two boys in the show. Marian’s younger brother, the pre-teen Winthrop, is afflicted with a stutter and a lisp, which is one reason why he’s so miserable for most of the first act. And yet, believe it or not, Willson originally conceived to Winthrop as an epileptic. That was deemed too severe for an Eisenhower-era musical, and the comparatively more benign stuttering took its place.

The Broadway musical has dealt with many serious issues in the half-century since The Music Man debuted. So Leap of Faith's bookwriters Janus Cercone and Warren Leight could give Jake an affliction far more serious than Winthrop’s: he can no longer walk as result of the car crash that killed his father.

We’re not told what killed Winthrop’s dad, but because it’s not mentioned, we can infer that it wasn’t as dramatic, unexpected and as quick as the accident that took Jake’s father from him three years ago.

Fatherless lads are often vulnerable and easy prey for charismatic con-men. Winthrop believes that Harold will start a marching band, but Jake has a far greater and more impossible hope: Jonas will be able to convince God to have him walk again. That leads to a sad irony: Marla has all along been telling Jake to have faith that he’ll someday walk again. Now the lad can’t understand why his mother is resisting a man who’s telling him the same thing.

Jonas already has his out when Jake isn’t cured. As he always says of townspeople, “If they don’t get the miracle, it’s their fault because they didn’t believe enough.” At least with Harold, everyone in town went home with a band uniform and a musical instrument, both of which could be sold or pawned. The people of Sweetwater will get nothing for their money.

As an imposter, Harold is – pun intended – a one-man band. The closest that he has to a confederate is Marcellus, who saw him perpetrate scams in other towns, but will now keep his mouth shut to River Citians. In Leap of Faith, Jonas’ sister Sam (as in Samantha) says of his burgeoning relationship with Marla and Jake, “You start caring about too many people, and our whole thing goes straight to hell.” This is a clever move on the part of Cercone and Leight: making Sam the real villain keeps us from hating Jonas.

As Marla’s resistance decreases, Cercone and Leight bring in Isaiah, the son and brother of two of Jonas’ followers. Isaiah reminds the women that his father was a real and sincere preacher, albeit unsuccessful. (Even in matters of religion, it seems, nice guys finish last.) Isaiah asks “Why is Jonas afraid to take that leap, to believe there is something larger -- or dare to believe that there is something greater than himself?” Indeed Jonas does before the show ends.

Your Jonas will have to jump over one hurdle that Harold didn’t: he must do a few rudimentary magic tricks, such as the one where he can make a row of scarves change color. All Harold Hill had to do in “76 Trombones” was take off his bland jacket and turn it inside out so it became a band jacket.

Gospel music ameliorates that we’re dealing with an anti-hero, and Alan Menken gives us a good dose of it. No fewer than six numbers have that tambourine-slamming, gimme-that-ol’-time-religion music that will be more than good enough for your audiences – let alone your cast. One of the best assets of gospel-tinged music is that it’s fun and ennervating to sing.

And why does a full third of the score utilize a gospel choir? Leap of Faith is structured as a genuine revival meeting that takes place in the very theater where you’ll produce the show. As a result, don’t be above getting those baskets on long poles that are found in every church and having your ensemble members go up and down each row of seats to collect. Perhaps some theatergoers might put some money in the basket which will help defray your expenses.

Or does that crass suggestion make me sound too much like Jonas Nightingale?

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.