Filichia Features: There’s a Parade in Philadelphia

Filichia Features: There’s a Parade in Philadelphia

Directors of Parade must cringe numerous times when they witness their production’s first preview.

Directors of Parade must cringe numerous times when they witness their production’s first preview.

They often see that after many of Jason Robert Brown’s songs end, the audience doesn’t applaud – not right away, anyway.

And while those seconds of silence pass, directors must wonder and worry. Is the crowd responding to this story of Leo Frank, the pencil factory superintendent who’s accused of murdering Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old worker?

Here at the Arden Theatre Company in Philadelphia, director Terrence J. Nolen sees it happening again. Oh, the theatergoers eventually do applaud, but only after they’ve had time to digest what they’ve just seen and heard. And that takes a few long seconds. Parade is, after all, a hard-hitting musical that isn’t afraid to point accusing fingers at the people who deserved them for what happened to Leo Frank 100 years ago in Atlanta. So audience members aren’t sure if they should applaud many numbers that involve sober themes or are sung by outright villains.

But if directors can wait out those difficult, silent seconds, they will find their audience eventually applauding and appreciating the success that both Brown and his bookwriter Alfred Uhry have had in telling this torturously difficult tale.

Nolen has tried to get his audience in the right mind-set before the show starts. He has some ancillary facts projected onto a movie screen that dominates the stage. Some pieces of information won’t strike all theatergoers as pleasing: “In 2001, citizens of Mississippi voted on whether to keep the Confederate flag as part of the state flag, and passed two-to-one.” Others are more encouraging: “In 2012, a Tennessee high school senior was barred from the prom for wearing a dress that resembled a Confederate flag.” These slides and other show how far – or not so far – we’ve come since 1913, when a great miscarriage of justice took place in Atlanta.

That screen is also useful because Parade lends itself to documentary footage. Jorge Cousineau has designed or accumulated film that has the look of Matthew Brady photographs, purposely grainy with an occasional vertical white line that indicates old and damaged film.

Cousineau also provides live-streamed footage of Leo in his jail cell and of Mary when she’s remembered at the trial. If your theater company has a technical marvel who can arrange anything like this, count your blessings instead of sheep and put him or her to work.

The first parade we see takes place in 1862, as the projection on the screen tells us. Young Solider is intent on protecting “The Old Red Hills of Home” in the Civil War. Once he finishes and walks off, Old Soldier hobbles on for the next parade: one that commemorates Confederate Memorial Day.

In the original Broadway production, Old Soldier had his right leg arched back and wore a peg-leg device to show he’d had an amputation. If that’s too complicated for your theater, do what Nolen did: over Old Soldier’s pants, put a leg-brace that suggests an amputation.

But Nolen delayed showing a slide that said the date was now April 26, 1913. That date should be displayed before Old Soldier comes on, so that the audience can understand that this amputated wreck is the remains of cocky Young Soldier who 51 years earlier would see that the Yankees “paid for what they’ve wrought.”

Leo Frank, a Brooklyn Jew who reluctantly came to Atlanta here because of business, is stunned that people would celebrate a losing cause. What the Confederate Memorial Day Parade also does, unfortunately, is keep alive the idea that the South is one land and the North another. And while Leo has sensed that in the four years he’s lived here, he’ll learn that lesson much more deeply in the days and years to come.

Ben Dibble is appropriately dignified and controlled as Leo, even as he bickers with his wife Lucille about their life down South. He tosses off “I’ll be home for dinner” which, as it turns out, won’t be true. On his way to work, Leo sings “How Can I Call This Home?” which Dibble delivers with the requisite mystification and, wisely, no self-pity.

We next meet Mary with Frankie, the teen who’s pursuing her. Unfortunately, Nolen cast an actress who seemed too old for the role. The program revealed that Kathryn Brunner was no kid; she’d already played Val, the successful plastic surgery patient in A Chorus Line.

Not having a convincing 13-year-old results in two problems: Frankie is supposed to be older, wiser, more experienced and even predatory -- but he doesn’t seem so here when romancing a twentysomething. More to the point, if Mary isn’t young enough, she doesn’t strike the audience as a vulnerable young lass, but simply as an actress doing her job. The audience can’t become as emotionally involved when the “girl” isn’t girlish. So cast young. (Mary doesn’t have all that much to do, so you can certainly find a teen who can do it.)

When the police arrive after the murder, Dibble asks “What is it?” in a most nervous manner. Yes, some people do become unnerved simply at the sight of blue uniforms. Having him taken aback was a good choice for another reason: at this point, the audience has no idea if this show will tell of a meek man who is indeed a killer. Thus, theatergoers could even infer that Leo is guilty from this delivery; if you can keep them guessing, the more suspenseful your production will be.

Thom Weaver’s lighting gets very dark here, and the policemen’s faces are only lit by flashlights that are pointed at Mary’s body. Nevertheless, there’s enough wattage for us to see the skepticism in the cops’ faces and the frightened expression on Leo’s face that passes for guilt.

Dibble staunchly endeavors to show all who have imprisoned him that he will not seem worried because he believes that the truth will set him free. Then he loses that confidence when Lucille tells him what he doesn’t want to hear: she won’t attend the trial, because she wouldn’t be able to face Mary’s mother. Uhry subtly but distinctly has Leo convey that if she isn’t there, people will assume that he must be guilty. Lucille sees his point – and sees what her life will be for the foreseeable future.

Jennie Eisenhower navigates well the transition and the commitment. Throughout the degrading trial, Eisenhower has Lucille hold on to her dignity and makes us increasingly admire her for it.

As Governor John Slaton, Scott Greer shows a man less concerned with justice and more intent on having this matter settled quickly to keep everyone’s volcanic-level tempers from erupting. The pressure that he places on District Attorney Hugh Dorsey forces the man to look for any way to get an easy conviction. Tony Lawton shows the desperation of a man who’ll do anything to please his boss.

When Dorsey discovers that black janitor Jim Conley escaped from a chain gang, he tells him he’ll be returned unless he testifies against Frank. The irony: today people widely believe that Conley was Mary’s murderer.

But because Jim will lie his way through his entire testimony, he must seem well-rehearsed and just a little too polished when he relates his fabricated story. Derrick Cobey does just that.

Nolen directs the witnesses for the prosecution in such a way that we have sympathy for them even as they jump to conclusions. The director makes us see that these people need closure and will do anything to have it as soon as possible. This approach doesn’t by any means make them noble, but it does make them seem less vicious or prejudiced.

One of the most remarkable moments in Parade takes place when Mary Phagan’s devastated mother takes the stand. Sarah Gliko is most moving when she blames herself for “not doin’ more to protect her from men who are cruel.” And then, at song’s end, when the tears that have been brimming in theatergoers’ eyes are just about to flow down their cheeks, she looks at Leo and addresses him not by name, but by spitting out the word “Jew.”

When Cabaret began its pre-Broadway tryout in Boston in October, 1966, the Master of Ceremonies likened the looks of a gorilla to a Jew. There was much outrage from Hub audiences that lyricist Fred Ebb dropped the lyric. Jason Robert Brown doesn’t pull his punch, and gets the audience to gasp in horror. And while many songs by now had taken those extra seconds to get applause, this one got none at all. Expect that when you do your production.

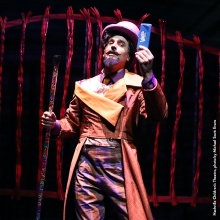

Arguably the greatest coup de théâtre of recent years occurs during the girls’ testimony. As they implicate Leo as a dirty middle-aged man, he gets up and illustrates what they say he. It has nothing to do with reality, but it’s just a way of their testimony coming to life in a dazzling song called “Come up to My Office.” Dibble becomes the sleazy, lizard-like being whom the girls describe, and rises to the galvanizing occasion.

And at the end of the first act, we get a very different kind of parade: one of joy now that Leo Frank has been convicted. Once again, Nolen makes his actors convey to us the intense need for Atlanta to begin healing. Yes, their values are damaged by their not caring enough that Leo may well be innocent; their town’s need to put this atrocity behind them is the musical’s secondary tragedy.

During Act Two, Nolen smartly directs Dibble and Eisenhower to be inured to his incarceration. They greet each other as if he’s welcoming her home from work; then they spar, because she wants to take action and he doesn’t want her to. This gives Eisenhower the chance to shine in “Do It Alone,” in which she sarcastically points out that it takes two.

Cousineau’s film shrewdly offers a marked difference when we get to the governor’s mansion; he uses color to show the opulence of the stately home and its vast green expanse of lawn and land.

If your company doesn’t have many talented dancers, Parade is an excellent show for you. Only here at the governor’s party is a dance required, and it’s a mere cakewalk that shows guests who don’t have many or any cares.

Greer shows that his conscience is getting to him even as the governor turns down Lucille’s request. Also deserving of praise is Sarah Gliko, who now returns as the governor’s wife and shows a smile of pride when he tries to do the right thing.

Brown wisely keeps Leo and Lucille from singing together until “This Is Not Over Yet,” and only then in two lines. They duet more in “All the Wasted Time.” Arden(t) theatergoers who’d already scanned their programs and had seen that title might have assumed that Leo and Lucille would ruminate about the lost years that he’d spent in prison. Brown showed greater insight by having Leo and Lucille sing about the wasted time before the murder, when they each took the other for granted and didn’t appreciate what marriage could offer.

This time the audience applauded with fervor the second this song ended.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.