Filichia Features: Moorestown’s Thoroughly Modern decision

Filichia Features: Moorestown’s Thoroughly Modern decision

Sitting in the Upper Elementary School in Moorestown, New Jersey, I’m looking forward to the audience reaction when the lights come up at a certain moment in Scene Four.

Sitting in the Upper Elementary School in Moorestown, New Jersey, I’m looking forward to the audience reaction when the lights come up at a certain moment in Scene Four.

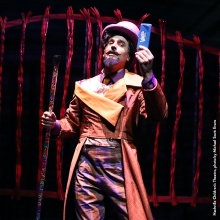

The Moorestown Theatre Company is offering Thoroughly Modern Millie, the 2001-02 Tony-winning musical. The ample-sized house is near-full on this Saturday night, and Laura Orlando has already won over the crowd in both the “Not for the Life of Me,” in which she insists on being au courant, and in the toes-tapping title song.

(Yes, I know the usual expression is toe-tapping. But when a song is as delicious as the Oscar-nominated “Thoroughly Modern Millie,” more than one toe starts tapping, doesn’t it? At least five get going and arguably ten are put into use.)

Everyone’s having a good time, which is only enhanced when Miller meets Jaclyn Biancaniello’s haughty Miss Dorothy and Debbi Nanni-Zacher’s comically evil Mrs. Meers. Now, in Scene Four, Millie will meet whom she believes to be her True Love: Mr. Trevor Graydon.

He’s played by Rick Williams, better known as a news anchor for ABC’s WPVI in nearby Philadelphia. Hmmm, maybe everyone’s watching the news on CBS, NBC or some other network, for Williams doesn’t get the recognition applause I expect. Maybe they’re just used to seeing him; he is on the theater’s board of trustees.

However, what I’m more interested in is seeing if any theatergoers turn to the people they’ve brought with them, looking in askance or even in horror after Millie gets one look at Trevor and purrs “Beau-ti-fullll.”

Because Ms. Orlando is white and Mr. Williams is black.

My binoculars show a sedate house that’s interested in hearing the story and the songs. I smile. There would have been a time when this casting would have been cause for concern, or even letters to the editors, picket signs and parents pulling their kids out of the production.

My binoculars show a sedate house that’s interested in hearing the story and the songs. I smile. There would have been a time when this casting would have been cause for concern, or even letters to the editors, picket signs and parents pulling their kids out of the production.

Not anymore, and we have almost a half-century of non-traditional casting to thank for it.

On Nov. 12, 1964, Bill Manhoff’s comedy The Owl and the Pussycat began previews on Broadway at what is now the August Wilson Theatre. Diana Sands, a black actress most famous for creating the role of Beneatha in A Raisin in the Sun, won the role of Doris -- although Manhoff had written the character with every intention of a white woman playing her.

But director Arthur Storch preferred Sands to all who auditioned and gave her the part. Some Broadway observers weren’t so impressed; after all, Doris was a prostitute, so the idea of a member of a minority making her living this way was hardly aggrandizing.

Two decisions eventually undercut that complaint. Storch hired white actress Rose Gregorio as Sands’ understudy. Then, in 1970, Barbra Streisand played Doris in the film. “Color-blind casting,” as it soon came to be known, was now a viable choice.

Little by little, the barriers were taken away. Actors and actresses were cast for ability first and race second. Talented people weren’t penalized because they weren’t of a certain color. While non-traditional casting started on the stages of Manhattan, it’s since been employed on professional, community, high school and middle-school stages all over the country and the world.

One of my favorite examples of the practice took place in 2004 at St. Peter’s High School in Jersey City. The show was Damn Yankees, and a white kid was playing old Joe Boyd, the Washington Senators’ fan who’d just sold his soul to the devil so that he could become an All-Star and rescue the team from last place. When he emerged as young, healthy and invincible baseball star-to-be Joe Hardy, he was now being played by a black young man.

All right, the director could have been making the comment that most of the baseball players who hold major league records are now black (since the sport began its own type of non-traditional casting in 1947). But I suspect that, like Storch did with The Owl and the Pussycat, the director was simply casting the auditioner who would be best for the part.

Have you tried non-traditional casting at your theater? Perhaps you’ve been afraid to because you don’t believe your community would support it. I’ll grant you that Moorestown must be a pretty terrific place; after all, in 2005 it was ranked no less than number one in Money magazine's list of “The 100 Best Places to Live in America.” It’s the hometown of Kevin Chamberlin, the original Broadway Horton in Seussical; Kate Shindle, Miss America 1998 and Donovan McNabb, once the star quarterback of the Philadelphia Eagles.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the Moorestown Theater Company figured prominently in Money magazine’s equation. The troupe was functioning at the time, for producing artistic director Mark Morgan began operations in 2003 with a production of Annie. The following year, he mounted three shows and five the year after that. That’s pretty impressive, until you discover that in 2013, the troupe’s eleventh year, no fewer than 15 productions were offered. Yes, 11 of them were shows with or for children (such as Guys and Dolls JR.), but is there any doubt that this theater is flourishing and is serving its community? It routinely wins South Jersey magazine’s readers’ polls for “Best Community Theater” and “Best Summer Camp” (yes, Morgan runs one of those, too) and – my personal favorite category of the bunch – “Best Boredom Buster for Kids.”

Morgan has employed non-traditional casting in the past, and even the theatergoers who might have blanched when he first introduced the concept to them have now grown accustomed to it and even expect it. That’s progress. If we stayed rigid to our traditions, then Pippin's Patina Miller wouldn’t have won a Tony this year in the role of Leading Player that was originally earmarked for a man.

Morgan has employed non-traditional casting in the past, and even the theatergoers who might have blanched when he first introduced the concept to them have now grown accustomed to it and even expect it. That’s progress. If we stayed rigid to our traditions, then Pippin's Patina Miller wouldn’t have won a Tony this year in the role of Leading Player that was originally earmarked for a man.

The comparatively small part of the theatergoing population who say “But it just isn’t real!” should be reminded that 1) the mansion you see onstage in Annie is far less ornate than a real mansion, 2) the beard on the Tevye in Fiddler On The Roof might not be one the actor has grown, 3) no one really dies when Sweeney Todd cuts a throat and 4) no one in real life starts singing out the blue. But we’re awfully glad they do, aren’t we?

I recall that in 1989, I took a cousin who’d never been inside a Broadway theater to see Into The Woods. When African-American Teresa Burrell’s Florinda was established as the sister of Caucasian Patricia Ben Peterson’s Cinderella, he said – nay, he virtually yelled out -- “But she’s black!” I lightly put my hand on his arm and said, “I’ll explain at intermission,” which I did.

Thirteen years later when we went to see Brian Stokes Mitchell as that Spanish writer Cervantes, he sat there and enjoyed the show.

The theater can be very proud of the fact that it – not film, not television – introduced non-traditional casting to the world. Once again, we’re ahead of the curve, for few theatergoers now feel they’re being thrown a curve ball when the see non-traditional casting.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.